Ian McEwan ~ Lessons

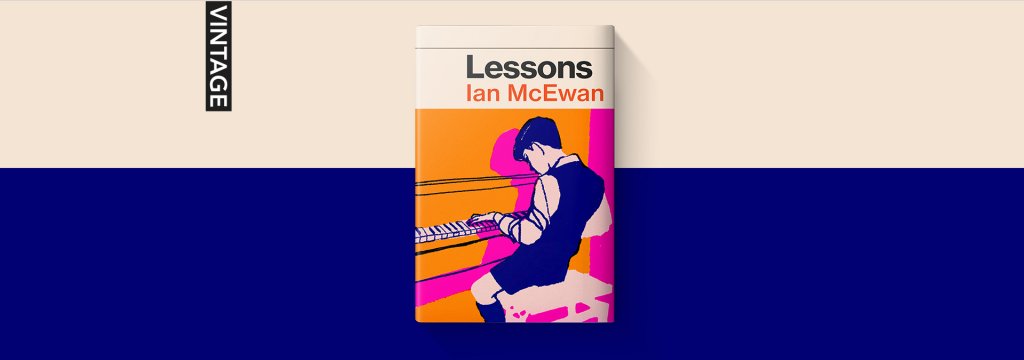

Ian McEwan, our foremost storyteller, has written an ambitious, mesmerising new novel, Lessons. The novel is a chronicle of our times - a powerful meditation on history and humanity told through the prism of one man’s lifetime.

Order from Jonathan Cape, Alfred A. Knopf, or Random House Canada. Translations are also available in numerous countries.

About Lessons:

When the world is still counting the cost of the Second World War and the Iron Curtain has closed, eleven-year-old Roland Baines's life is turned upside down. 2,000 miles from his mother's protective love, stranded at an unusual boarding school, his vulnerability attracts piano teacher Miss Miriam Cornell, leaving scars as well as a memory of love that will never fade.

Now, when his wife vanishes, leaving him alone with his tiny son, Roland is forced to confront the reality of his restless existence. As the radiation from Chernobyl spreads across Europe, he begins a search for answers that looks deep into his family history and will last for the rest of his life.

From the Suez Crisis to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall to the current pandemic and climate change, Roland sometimes rides with the tide of history, but more often struggles against it. Haunted by lost opportunities, he seeks solace through every possible means - music, literature, friends, sex, politics and, finally, love cut tragically short, then love ultimately redeemed. His journey raises important questions for us all. Can we take full charge of the course of our lives without damage to others? How do global events beyond our control shape our lives and our memories? And what can we really learn from the traumas of the past?

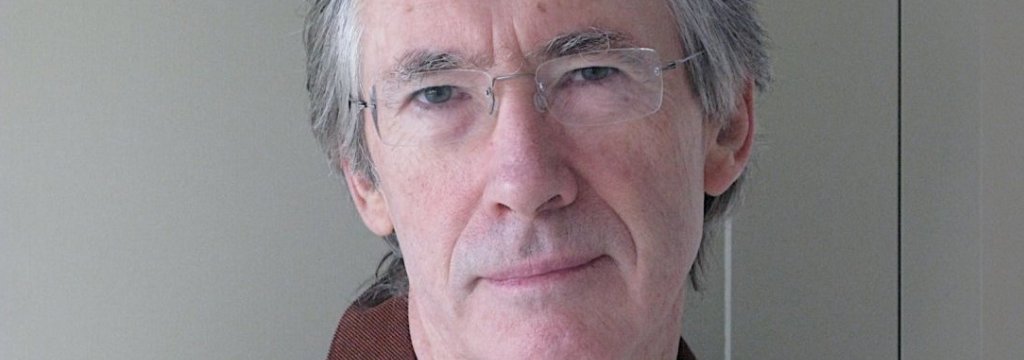

About Ian McEwan:

Ian McEwan’s works have earned him worldwide critical acclaim. He won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1976 for his first collection of short stories First Love, Last Rites; the Whitbread Novel Award (1987) and the Prix

Fémina Etranger (1993) for The Child in Time; and Germany's Shakespeare Prize in 1999. He has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction numerous times, winning the award for Amsterdam in 1998. His novel Atonement received the WH Smith Literary Award (2002), National Book Critics' Circle Fiction Award (2003), Los Angeles Times Prize for Fiction (2003), and the Santiago Prize for the European Novel (2004). Atonement was also made into an Oscar-winning film.

In 2006, Ian McEwan won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his novel Saturday and his novel On Chesil Beach was named Galaxy Book of the Year at the 2008 British Book Awards where McEwan was also named Reader's Digest Author of the Year. Solar won The Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction in 2010 and Sweet Tooth won the Paddy Power Political Fiction Book of the Year award in 2012. Ian McEwan was awarded a CBE in 2000. In 2014 he was awarded the Bodleian Medal.